By Dimi Sandu, Head of Solutions Engineering (EMEA)

You have probably heard the phrase ‘punch a hole through the firewall’ and, if you are not an IT professional, wondered what that might exactly mean. In this article, we will provide a brief overview of this essential piece of equipment that keeps your networks safe.

First of all, if you are new to networking, I would recommend you read this article here, detailing a few important devices that, linked together, create the networks we all rely to work when using our computers and phones. There are a few key concepts that we will use:

End device - laptops/PCs/mobile phones, but also other office equipment such as printers and desk phones;

Server - a specialized computer that has a narrow purpose (e.g. hosting one or a few applications, or a database), built for power and performance, serving multiple end devices (or clients) at the same time; they are either managed and run by a business themselves, and physically placed in their data center, or offered as part of a service, usually connected to the Internet (e.g. Office365, Zoom, Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services);

LAN - short for Local Area Network, comprised of the equipment that interconnects the end devices between themselves, and together with the rest of the Internet; this is usually owned and managed by the business themselves, although maintenance can be outsourced;

WAN - short for Wide Area Network, the network or networks owned and managed by ISPs (Internet Service Providers), connecting multiple LANs together; the most known and publicly accessible infrastructure, a mesh of different providers, is called the Internet; however, most ISPs also do provide private circuits, built on top of a totally separated network; the latter tend to be more expensive, but guarantee a certain level of service that cannot be achieved by a public shared network like the Internet;

Traffic flows - a stream of information, usually associated with an application (e.g. making a Zoom call will result in a constant flow of data between you and the destination, for the duration of that session).

Note that, throughout this article, we will define the directions of the traffic flows in the following way:

- Downstream: from the Internet to the end device (e.g. downloading a file from a server)

- Upstream: from the end device to a destination on the Internet (e.g. uploading a file to Google Drive)

So where do the firewalls come in?

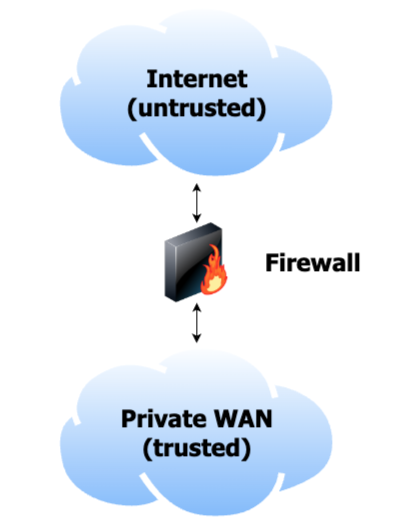

In simple terms, firewalls are here to protect the ‘trusted’ LAN (trusted because each business can, in theory, have full visibility, control access and block any malicious activity) from the ‘untrusted’ Internet. Any hacker can host their infrastructure on the Internet, launching their attack campaigns from there, as nobody owns this public network in its entirety.

Diagram 1: The firewall, sitting between the LAN and the Internet

Almost all hacking activities are malicious in nature, targeted at things such as:

- Extracting sensitive data (e.g. bank account details, email login details)

- Impacting the ability of a business to operate (e.g. a denial of service attack that shuts down or slows a website or application down, to the point where consumers cannot use it)

- Extracting revenue (e.g. locking devices and demanding a ransom in return for the data)

Note: some hackers, called ethical or white hat, operate solely for the benefit of the business, testing their networks and applications to uncover vulnerabilities, giving the businesses a chance to fix them before someone with malicious intent exploits them

Since the inception of the Internet, firewalls have been an integral part of networks, securing them from ever-evolving threats. It does so by analyzing and filtering traffic, gaining an in-depth understanding of all the flows (including sources, destinations, and applications), and utilizing its intelligence to block dangerous or unwanted ones.

A great example is that of a user clicking on a link inside a spam email. If left unfiltered, the webpage would display, prompting the user to disclose their credentials to the attacker, or injecting viruses through compromised software. Most enterprise firewalls will recognize the traffic is going to a dangerous destination, blocking it and displaying warnings to the end user.

Modern firewalls, also called UTMs (Unified Threat Managers) have a myriad of security functions besides inspecting and blocking dangerous traffic, such as:

- content filtering (blocking access to certain websites or categories of websites),

- malware and virus detection (scanning incoming files and comparing them to a known database),

- sandboxing (using a virtual environment to ‘detonate’/run an unknown file, and inspecting its behavior),

- data loss prevention (stopping the sharing of sensitive data outside the organization, willingly or by mistake),

- shadow IT detection (detecting and stopping the use of any personal applications for work purposes, in order to make sure all the tools that touch corporate data are approved and follow a standard).

Although traditionally firewalls and UTMs have been on-prem devices, installed and maintained at each location that has an Internet connection (or breakout), it is more and more common to outsource this function to some well known cloud providers (such as Zscaler and Palo Alto Prisma), that can offer the same functionality remotely. The latter removes the sometimes large CAPEX cost of purchasing and installing your own firewalls, billing instead based on traffic volumes.

What does it mean to punch holes in the firewall?

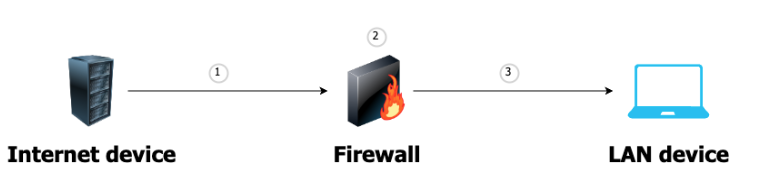

So now that you know why a firewall is critical for all the locations you break out to the Internet, it is time to answer one final question, that of ‘punching holes in the firewall’. In simple terms, by default, the firewall allows traffic flows originating from the LAN, while blocking the ones from the WAN. Once a client initiates traffic locally, destined for the Internet, a session is established, allowing for a bi-directional flow of traffic (the return traffic is not blocked). If the traffic is initiated from the Internet (e.g. an attacker trying to connect to a local machine), it is automatically blocked.

In order to allow Internet/remote traffic to be received, the administrators can create what is called ‘port forwarding’, creating a rule allowing specific traffic to traverse the firewall, even if the communication was not initiated locally. This is common in security systems, as traditionally they have not been designed to be accessed outside the LAN, and subsequent products allowed that to happen. But, as the NVR is not coded to reach out to the Internet, it has to receive it instead, making the newly created firewall hole a necessity. Sadly, such configurations create vulnerabilities inside the device, which now has openings that can potentially be exploited by trained hackers and attackers.

Diagram 2: Port forwarding in action, with a device on the Internet initiating traffic (1), the firewall not blocking it as per default (2), instead sending the traffic to a predefined local host (3)

Bottom line, if possible, make sure to never use port forwarding.

For more videos on physical security & networking, follow Dimi on his YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/DimitrieSanduTech